Diverging from tech subjects, I can’t really remember where I heard about Poul Anderson’s book “Three Hearts and Three Lions”. Somewhere it was recommended to me through some some hypertext rabbit hole that I ended up falling down. I managed to find a digital copy through my various means, and than it sat on my digital book shelf, collected virtual dust. Time passed, and, occasionally, as I scrolled through my backlog of reading material, I would see the title and think, “hmmm, yes. I should really get to that one.” But then something else would catch my eye, and I would forget about it again. Anderson is one of those authors that you find on the shelves of used book stores — remember those? — who had a writing career that spanned through the 20th century and into the 21st. But he’s not a guy that I grew up with like Jack Vance, J.P. Blaylock, Tolkien or Lovecraft, nor was he ever recommended to me when I was kid.

About a month ago I started watching a bunch of videos, detailing the history of D&D. I’ve been fascinated by role playing games since I was kid; over time my interest has pivoted away from focus on the fantasy or sci-fi elements to general narrative construction and story telling. I’m not sure why my mind works like this, but I get really into the development of anything that catches my attention; I want to see how it started and how it changed over time. I want to understand it within its context and go deep. I do this with tech and math too.

So, there I was, watching video essay after video essay about Gary Gygax and the rise of his table top fantasy war game that turned into D&D as we know it; until I came across a video about the D&D version of the troll.

When you see the troll in the original monster manual and you know anything about trolls in Scandinavian myths, you’ll notice that they look very different. Typical trolls from myth, are shaggy, brutish humanoids — kind of half-beast and half-man and more than a bit ape-like — as in the troll from “Three Billy Goats Gruff”. They’re capable of speech and tool use. They’re not very intelligent, but they’re also not animals. D&D trolls, on the other hand, are truly monstrous and alien; they also have the weird ability to regenerate, and their severed limbs can go on fighting, even rejoin the body; they are some kind of protean monster with hollow eyes. Where did Gygax get this version of the troll? “Three Hearts and Three Lions”.

I knew about Jack Vance’s influence on Gygax and his magic system — often referred to as Vancian — and I have read all the Dying Earth books — some of them multiple times — while growing up: “The Dying Earth”, “Eyes of the Overworld”, “Cudgel’s Saga”, and “Rhialto the Marvelous”. Once I was through with this essay about trolls — wherein the presenter read a passage from Anderson’s book — I decided to descend into my digital study and pull out the volume.

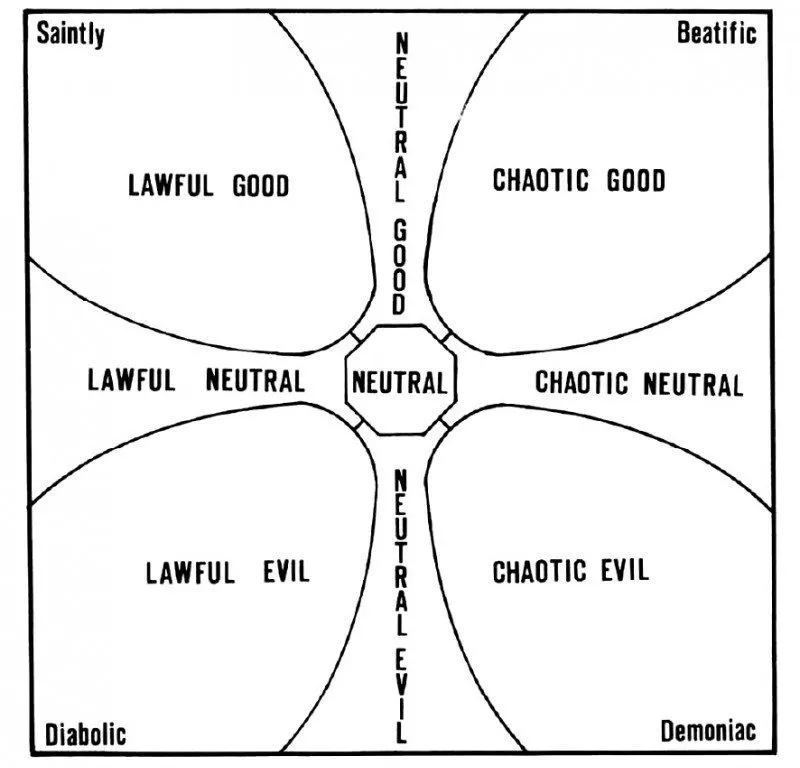

“Three Hearts and Three Lions” tells the story of Holger Carlsen: a Dane who decides to join the underground resistance in WWII and finds himself teleported to a medieval world where the Carolingian legends, monsters and magic are real. Not only did I immediately see where Gygax was pulling from, but also a lot of other fantasy authors. Anderson sets up a great conflict between the forces of Law and Chaos; I know that before the current alignment system in D&D, split into the 9 different categories, there were originally just two: Law and Chaos. This idea comes up again and again, most notably in Moorcock’s “Eternal Champion” books.

The story even plays out like a D&D campaign. Our hero appears in a wood where he finds a war horse and full set of gear waiting for him. As the story continues, he collects allies, has various encounters, finds his way through kingdoms, forests and hamlets and eventually receives a quest to seek a magic sword in a defiled church (St. Grimmins on the Wold totally reminds me of “Diablo” and I was a bit disappointed that the story wrapped up so quickly at this location). Anderson never takes Holger into the dark night of the soul, though; the Dane faces plenty of opposition, but he handily gets himself out of each sticky wicket. A lot of the creatures that would later appear in the first Monster Manual show up here, as well as a lot of tropes like having an underwater adventure where the characters can breath with magic, or going into a magic shop where we get the next plot token from some old geezer who could be wise, or a total quack. It’s all there.

A quick word on the language in this book. If I had tried to read this as a teenager, I don’t think I would have gotten very far. There’s a lot of French, German and Latin that appears in this book; two of the characters speak in a weird brogue that is phonetically Scottish, but ropes in some German and old English. Reading a lot of this book is a bit like reading “The Wake” by Paul Kingsnorth (2014): sometimes you have to read it out loud to get at the meaning. Since I was angry youth, I’ve lived 2 years in France and almost a decade in Germany; I’ve taught myself some Latin and Classical Greek; I’ve been around. So, what would have been a very challenging text back then is now just a delight.

All and all, the folks that are going to get into this book are a very small niche. But, if you’re in the crazy Venn diagram of language enthusiast, fantasy fan, and classic D&D nerd, then you will get a lot out of this book and I recommend it. Admittedly, there are not a lot of people that fit into that intersection.

Post a Comment